Now Reading: In Conversation with Dr. Leggie L. Boone, Ph.D., Forensic Latent Fingerprint Analyst, Polk County Sheriff’s Office, Florida, U.S.

-

01

In Conversation with Dr. Leggie L. Boone, Ph.D., Forensic Latent Fingerprint Analyst, Polk County Sheriff’s Office, Florida, U.S.

In Conversation with Dr. Leggie L. Boone, Ph.D., Forensic Latent Fingerprint Analyst, Polk County Sheriff’s Office, Florida, U.S.

Dr. Leggie [Leh ‘jee] Boone is a Forensic Analyst, Author, and Educator. Dr. Boone’s main fields of interest are vicarious traumatization, organizational support and civilian relations, implicit bias in crime scene attendance, the personal impact of law enforcement suicide, and active dreaming. Her research has explored how trauma exposure, tenure, and education influence performance effectiveness and perceived organizational support for crime scene investigators. She has also explored contributors to law enforcement suicide and the policies accessible for awareness and intervention.

Dr. Boone has worked as an educator in Baltimore County, Maryland schools and colleges, teaching sciences including Biology, Environmental Science, Paramedical Biology, and Forensic Science. Her crime scene and teaching experiences allowed Dr. Boone to collaborate on publishing the forensic textbook and virtual component, So You Want to Be a CSI, with two other former CSIs. Dr. Boone also published Fox Tails: Short, Short Stories Written While Puppysitting, she has multiple poems and song lyrics published in books and magazines. Dr. Boone currently works as an adjunct professor at Keiser University in Florida, in the Crime Scene Technology program and as a Senior Adjunct Faculty member for the Sherlock Institute of Forensic Sciences, India. She has also been an invited speaker at many international conferences, including those sponsored by the Global Scientific Guild, Worldwide Association of Women Forensic Experts, and the Caribbean Association of Forensic Sciences.

What inspired you to join the field of Forensic Science, and what motivates you to continue along with this path?

Like many, my initial plan growing up was nothing like what I ended up doing. I wanted to be a veterinarian and travel to remote places tagging animals. In 1986, I came across my first wordle – a poster titled What Can I Do with a Biology Degree. I acquired a copy and found several options in case the animal track did not pan out. Forensic Technician was one of the titles I highlighted on the poster. I did work at the Baltimore Zoo out of college but met a neighbour who introduced me to crime scene photos, telling me about his job. I applied and while I waited through the hiring process, I volunteered with the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner near the University of Maryland in Baltimore. My curiosity and my analytical mentality peaked. The comradery of the crime scene family kept me interested and growing. I learned a great deal about my city, the nature of crime and law enforcement, and about myself. I have stayed in this interesting community of forensic minds because I enjoy learning and teaching aspects of crime scene investigation as it evolves, with the hope of sharing my experiences and motivating others to enjoy the subtle rewards of public service through helping those who have endured tragic or traumatic situations.

At present, you are working as a Forensic Analyst, an Adjunct Professor at Keiser University, and also you have worked as CSI. How were these roles different from each other? What were the challenges that you faced in each role?

As a CSI, I had mobility. I gained confidence in getting to know Baltimore City and County through the calls for service. I was a Crime Scene Investigator before being a CSI was highlighted by the television series and similar programs that showcased the techniques applied in forensic disciplines. I learned a great deal on the job and also attended a Crime Scene training with 20-25 others from multiple agencies. After roughly a year on my own, I was training other new mobile technicians. I thought that was odd, but my supervision saw something in me that I didn’t recognize. I transferred to the Baltimore County Police Department in the position of Forensic Services Supervisor. While there, I became an adjunct professor at the Community College of Baltimore County.

My challenges were rarely job-related: I left crime scene work shortly after my daughter was born due to the combination of strenuous, unpredictable work hours, a failing marriage, and the onset of what I now understand was vicarious trauma. When I left crime scene work, I chose to become a full-time educator or divine intervention chose education for me. I would have never thought I would have become a teacher. This role grounded me in a completely different routine- I had regular daytime hours, no shift changes, and summers, weekends, and holidays off. That was a huge difference. I felt like taking classes along with teaching became my therapy. I taught Biology, Environmental Science, Paramedical Biology, Biotechnology, and Forensic Science in Baltimore County high schools. Teaching revealed a lot for me as I got to know more about teenagers who experienced group homes, abuse, rape and molestation, absent parents, and many situations I had never expected them to share. Hearing their stories was challenging for me. I became a therapist through my own therapy. The only true achievement through those years of teaching was the opportunity to be a role model, encourager, motherly supporter, and listener for young people who were missing those facets in their lives. I didn’t realize that I would be that person to so many, but I appreciated where God had placed me.

As a Forensic Analyst, I was able to apply what I had learned from crime scenes, in my studies to reinforce the subjects I taught, and through furthering my education in graduate programs. As a Latent Print Examiner, I had to gain confidence in a whole other discipline and absorb the fact that my skills would be determining factors in someone else’s life. I could not make any errors and that was a different type of pressure and expectation that neither attending crime scenes nor teaching young people demanded. In all positions, we try to limit our errors, but in forensic analyses, the conclusion could be life-changing. Even though every case worked is technically and administratively reviewed by another qualified examiner, I want to make every effort to make the best conclusion for each item of evidence I examine. Having this elevated level of expectation is a challenge requiring a willingness to uphold personal standards, standards of my law enforcement agency, and standards of my forensic discipline because one erroneous conclusion could damage the credibility of each.

What are the most important things to consider when conducting a crime scene investigation?

I believe that conducting a crime scene investigation requires that the CSI pull from several resources and reserves of knowledge and training. Staying up to date on advancements in technology, changes in the standards of each discipline applied and continuing education is most important for the CSI. When conducting an investigation, the CSI must understand that this incident (whether a tragedy through assault, abuse, death, burglary, robbery, arson, or other) is this victim’s worse moment or day. Even though we, as CSIs, may attend crime scene after crime scene, each victim is having that issue for possibly the first time and their life and psyche are altered for a lifetime because of a violation of their personal space, privacy, or possessions.

What is the most interesting thing you’ve encountered during an investigation? And what was the case you found most challenging to solve?

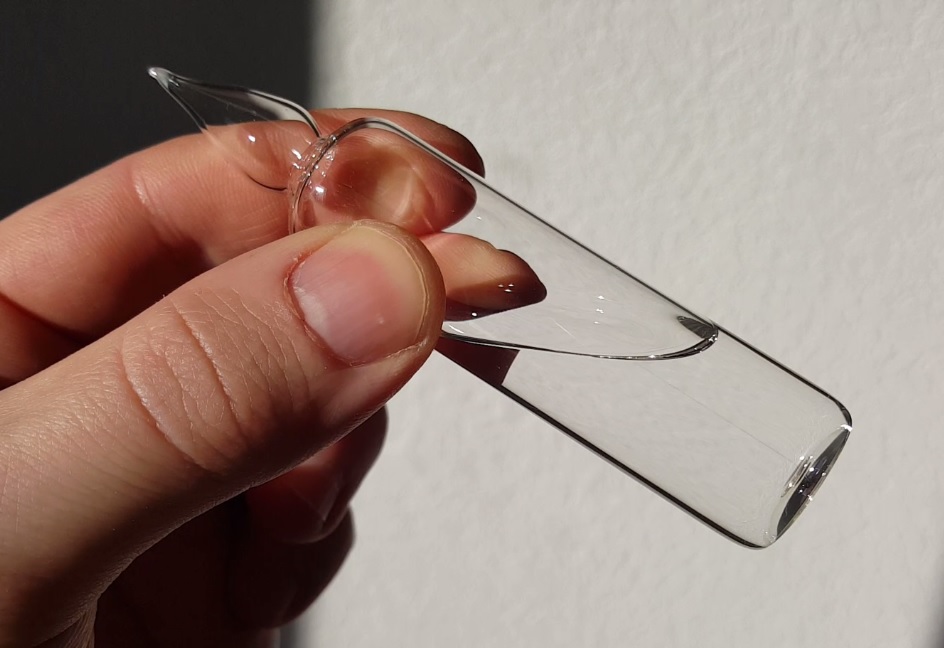

I have contributed to the investigation of thousands of crime scenes in a combination of 14 years as a CSI and 10 years analyzing evidence. Identifying the most interesting case is difficult. I have had the opportunity to attend and assist with autopsies of varying natures and degrees of mutilation. Seeing foreign objects in bodies has been morbidly interesting. Also, applying techniques that are not used on an average day made the job more fascinating at times. I have seen the decomposed, sloughed hand skin put on like a glove in an attempt to get fingerprints. I have seen multiple autoerotic asphyxiation victims. The scene that is by far my most interesting has been the one that I dreamed about the morning before I was dispatched to the location. A homicide had occurred, and the victim had been buried face down in a shallow grave in a vacant lot. The case was solved, not specifically through my efforts, but it was thoroughly challenging to function with the premonition of the location and details on my mind. Also, it was the only scene where I had to be assisted by a paramedic for dizziness due to the 105-degree Florida August heat with an equally hot uniform.

Dr. Boone your main fields of interest are vicarious traumatization, organizational support and civilian relations, implicit bias in crime scene attendance, personal impact of law enforcement suicide, and so on. Can you tell us more about vicarious traumatization? What do you think is the most effective way of treating vicarious trauma? What are the best measures that organizations should include to prevent vicarious traumatization among crime scene investigators?

As recorded in studies of therapist response to frequent interaction of clients sharing their emotional trauma, vicarious traumatization was introduced by McCann and Pearlman in 1990 as a psychological response of chronic symptomatic distress to indirect trauma experienced by those close to a critical incident. It is my belief that the CSI potentially has more frequent exposure to traumatic scenes than the sworn officer in many places. (The definition of ‘traumatic’ is highly subjective, therefore, I would describe traumatic as a scene that triggers an emotional response or that may be visually graphic.) Due to the typical limitations of zone/district/region assignments, sworn agents of the law are responsible for covering their area. The CSI often has a zone, district, or region; however, the number of CSI personnel is exponentially lower than that of the sworn personnel, therefore a CSI would be responsible for multiple districts within the city, county, or region. With that logic, add in the crime rate, and the CSI will attend a higher number of violent scenes, stay for longer periods of time, and review the evidence from those scenes for extended hours, not including revisiting the photos and evidence if the offense is presented in court. I must state that all first responders, second responders, or those indirectly encountering the tragedies of others are susceptible to vicarious traumatization.

Vicarious trauma is not often diagnosed and may not be recognized, due to the individual factors involved in the psyche. Due to the level of subjectivity in determining vicarious trauma, as well as burnout, and compassion fatigue, treatment is also individual and subjective. I believe awareness that emotional response, whether visible or internal, may be triggered by attending scenes of tragedies is important. The response may impact job performance or may evolve into desensitization. No response to traumatic scenes is in essence a response, also. Awareness and identifying coping strategies that are meaningful for the individual may be effective ways to manage vicarious trauma. Coping strategies could include any variety of actions- prayer, meditation, exercise, physical exertion, hobbies, time with family or friends, positive self-talk, music, reading, or others. Any positive activity that allows the mind to decompress from the stress of a critical incident could be helpful.

Offering awareness information and also, acknowledging that we each may respond to trauma in different ways are important first steps for an organization. Some of us may not express our feelings, internalizing or electing negative coping strategies. Our global culture is changing and encouraging mindfulness and relaying a wide range of resources on mental health. The stigma of sharing a need for psychological help, whether that help comes in the form of a sympathetic ear or a professionally organized plan, has been deeply imbedded in society, and noticeably in law enforcement culture. A law enforcement organization that wishes to retain and support their employees should consider including or encouraging the use of an employee assistance program, provide regular training or announcements to advise of preventive measures for stress management, and should maintain policies of confidentiality so that employees do not feel as though their expressed need is a sole indication of an inability to perform the duties of the position. The installation of a Critical Incident Stress Management Team, which includes access to a professional psychologist and trained peers, is another mechanism an agency may consider. Peer support and supervisor support are also vital options of which organizations should remind their members.

In your opinion, is the criminal justice system currently working fine, or does it need a lot of improvement?

There is definitely room for improvement in the criminal justice system. I believe that there is far too much inconsistency with regards to penalties for crimes and too much weakness in policies and enforcement due to financial and racial disparagement. There are scores of situations of both illogical sentencing and impropriety regarding wealth and race, but I am not able to share them here without presenting factual research.

How often are CSIs involved in investigating cold cases, and if so, do you have any success stories?

As a CSI, it has been rare that I have had the opportunity to assist in cold case re-investigation. In those instances, I had worked with senior homicide detectives in an effort to acquire funds to create a 3-dimensional representation of a scene, of the caliber of the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death- crime scene dioramas assembled by Frances Glessner Lee in the 1940s. We were not able to get support for funding. Other methods and tools came available that allowed more in-depth analyses of evidence (biological, latent print, shoe wear, etc.), however, I was not directly involved as a CSI. As a Forensic Analyst, I have been applying the updated algorithms of the automated fingerprint identification system (AFIS) to previously reviewed cases, as a form of quality assurance and I have been successful at identifying prints in 35 of the 150 that I have reviewed between my regular casework thus far. Although many of the identifications have been to the victims, there were a few suspects that were generated, too.

A key aspect of any investigation is the field officer’s expertise. If a crime is spread over a large area, then how do you collect and transport evidence to the lab in an effective manner?

When a scene covers a large area, I would request the assistance of other available CSIs or my supervision. As the primary CSI, I would request each person to handle specific aspects of the scene- photography, evidence measurements for sketching, collection, recording, or any other requirement. If there was no one available, I would enlist the aid of any officer or deputy who was available to accompany me throughout the process, to act as my recorder and assistant. Time is rarely the issue when it comes to scene processing, but lighting, weather, temperature, structural hazards, biohazards, media pressure, onlooker presence, or any combination of these can be issued. The goal must not be swayed by detective or victim pressure and impatience when we’re trying to find, document, and collect evidence of a crime. When evidence requires transport to a distant location, communication is key. Communication between agencies has rarely been my struggle. A phone call and an email would be exchanged to plan the transport of any evidence. Smaller agencies (many agencies, honestly) do not have full lab capabilities, so they rely on state and private labs for evidence analyses. Relationships are built between these agencies and the lab facilities to share policies and expectations for evidence transport, receipt, analysis, and retrieval. As an examiner now, my agency dictates when another agency can bring evidence and how much can be brought on each visit.

In modern times, the traditional criminal tactics evolved tremendously. In comparison to that, how have the investigation procedures evolved with this?

For many years, decisions for changes or improvements were slow-moving and often relied upon a statistical approach. The numbers of crimes, the quantities of evidence, the arrests, the convictions- all strategies focused on reducing the crime rate by increasing a factor here and a factor there. More recently, investigations are taking a more intel-driven approach. There has been a stronger push to return to community policing and engagement with citizens for a more accurate image of how to combat criminal behaviour. Law enforcement officers are being re-trained to listen and ask more questions to get a broader, yet more personal perspective from church leadership, community leaders, parents, people out and about, and attorneys. Hopefully, this approach will reduce the gang-related crime or deter the wayward follower from the path to jail, drug activity, or violent death.

As an Adjunct Professor, what are your key principles in training & educating the next generation of scientists?

Something that I am a strong proponent of is continuing education. I encourage every peer and every student to be a lifelong learner and take a class, listen to a webinar, and enroll in any opportunity that will allow them to network and pick up new information, strengthen or spark interests, or hone skills. There is a multitude of free or low-budget courses and webinars available through several different websites. Also, I recommend engaging with forensic organizations or organizations that share your interests. These affiliations offer great spaces to connect with like minds, exchange ideas, or provide training opportunities.

As the current generation of scientists gets involved in the growing variety of forensic disciplines, I encourage the development of observation skills along with the importance of being inquisitive. As we see and do the different tasks of our positions, question the methodology if it isn’t clear, use each moment as a chance to learn, apply that learning and continue to research where there may be gaps. That is how our fields grow and evolve.

Do you think virtual reality will be a useful tool in training students to become CSI?

Yes, emphatically. I am encouraged by this question because I have had the great opportunity to contribute to the organization of a virtual component for So You Want to Be a CSI, the forensic textbook which I co-authored. The goal of functionalizing this plan was to give the instructor a chance to put the students on task by having them individually walk through a virtual scene and completely handle it as a CSI. Due to the constraints of COVID and its effects, budget limitations, and personnel retention, providing a live, practical scene can be a daunting event, especially for the novice teacher, the non-practitioner, or the instructor with multiple sections of courses. There is no substitute for true crime scene attendance, yet, a virtual approach is cost-effective and can be assessed to gauge areas for improvement for the trainee or student.

What do you think the biggest problem is in law enforcement today? Here in America? And around the world? And how can we solve some of the problems that you mentioned?

For ages, trust in police has declined. Within law enforcement, agents are allowing feelings and personal emotions to interfere with purposefully fulfilling the duties of the job. Understanding emotional intelligence and applying that awareness and control in situations and scenes will allow a logical approach, a more respectful interaction, and possibly a more appropriate outcome. The community does not respect law enforcement and law enforcement does not respect the community. It is a national and worldwide problem. This problem is not new or recent, but continual. Social media is now capturing all of these emotions and these shared emotions are being challenged.

Since much of the variation in emotional intelligence, respect, and judgment stems from upbringing, personal experiences, trauma, relationships, and overall personality-shaping contributors, solutions would have to pull from all areas of development. A combination of parental and organizational accountability and acknowledgment, an understanding of Golden Rule values, and the institution of a regular (annual or biennial) psychological evaluation of law enforcement officials would be a grand start, in my opinion.

What’s the best advice you can give to young women trying to pursue a career in forensics?

My first recommendation for women entering forensic studies and disciplines is to build connections. Join forensic organizations and subscribe to their emails. Attend webinars and conferences. Get that business card and note where and when you received it. Ask questions. Talk to people who are doing the job you are interested in pursuing. As your network grows, you will grow and be exposed to more options. I also recommend that you continue your formal education if feasible. For-credit or not-for-credit courses are important. Never stop learning,

Yet another tidbit of advice is to be true to yourself- you don’t have to limit your womanhood to fit into the position. We know that men have historically dominated most fields, but we do not have to forfeit or suppress our womanhood to be great learners, performers, or leaders in this or any field. By nature, women are equipped to be analytical, inquisitive, and nurturing and these innate skills should be embraced and utilized in forensics. Suspend self-judgment and find that space in forensic science that fits you, your niche. In summation, stay connected, accept help, be the best woman you are meant to be, keep learning, and train the Next.

You have published textbooks, poems, and song lyrics as an author/co-author. How would you describe the stories/poems that you write? What is your motivation to write crime-solving fiction?

In my earliest days as a Mobile Unit Technician (AKA CSI), I wrote songs- music and lyrics, to distract myself from some of the scenes and from whatever life issue I thought I was experiencing. When I had downtime, I was always thinking of some project to keep my mind active and occupied. I sang in a couple of groups and on choirs and I had my lyrics copywritten, as an eventual legacy. I have rarely been without a pen and a notepad. The poetry came a little later, also as a tool of distraction or method of decompression, long before cell phone games, social media, and fidget spinners became available.

I continue to carry a notepad, making to-do lists or jotting down ideas and plans. I wish I could write “crime-solving fiction,” but my conscious mind is not half as creative as my sleeping mind. I dream vividly detailed dreams and have been recording them for more than 30 years. Some of the dreams have reflected my career in crime scenes, and I’ve awakened to draw rough sketches, outlining evidence and objects or furniture in the scene. I have also had dreams with classroom themes, fingerprints, and office themes, as well as sorority dreams. In the very near future, I will publish my dream series. I feel like I have been given these subconscious movies for a reason. My motivation to write is self-serving. It’s therapeutic and memory-enhancing. In my first psychology class at York College of Pennsylvania, many moons ago, a graphologist shared information about handwriting analysis. She reviewed a portion of my writing and told me that I would achieve what I set out to do, but that my absentmindedness would be a problem unless I wrote things down more. The seed had been planted years before that, but this new information was fertilizer. I truly write because I enjoy reading and I want to get my thoughts out of my head, and in front of me.

What are some everyday tips or tricks that you use to keep motivated or on a daily schedule?

I read Jeffrey Deaver’s books (author of The Bone Collector) for years and one of his characters shared that “if I stop moving, they’ll get me.” There was no real “they” in the story, only her struggles with her perfectionist mentality and need to impress the ghosts of her past. I sometimes feel that way, so I keep moving. I don’t believe I’m a perfectionist in any way, yet I strive to be the best ME that I can be. I walk when I talk in prayer at home, in the classroom before students arrive, and in my own office; I talk to my mother and my sweetheart frequently and I show and tell them and my daughter (and my five pets) that I love them. I recommend giving as a true means of fulfillment. Giving time, giving your talent, or giving in whatever way you can give. Teaching is one way to share what I have learned. I believe that knowledge should not be hoarded. I also believe that we should always be preparing for the next Next. By that I mean, the Next person who will step in and continue what I have started or continued, and the person who could come right beside or behind them. Our employment and skill are temporary adhesives and to keep that field, that discipline, and that story going, we need to share what we know and eventually step aside and see the growth as our next Next steps. They may continue or revise the plan, but that is a good thing. Seeing those that I have encountered through the classroom, training, or brief information exchanges move forward in greatness is motivational for me.

Having worked for almost 3 decades in the Forensic Domain do you still wish to contribute to this domain? How?

I feel like teaching is a great way to contribute and connect with the growing forensic community. I love attending and participating in symposiums and conferences, networking and learning, as well as gaining insight into new and transitioning practices. I am always listening, taking notes, and asking questions, hoping to build relationships of mutual, professional benefit. I have made some exceptional connections through forensic associations and conferences, and with LinkedIn groups and individuals, that have led to great opportunities. My association with Legal Desire, involvement in international conference presentations, podcast interviews, book collaborations, dissertation coaching, and more have branched from my network of LinkedIn professionals.

I established Generation ForSciTe as my family business to expand on our varying creativity with the primary goal of enriching others in the forensic realm. The ‘Generation’ represents the four generations of Leggie (my great grandmother, mother, myself, and my daughter). ‘ForSciTe’ stands for Forensic Science and Technology, which was a student club I created when I taught high school sciences. I wanted to instill the importance of sciences and incorporate its relationship with technology while playing on the word foresight. Generation ForSciTe encompasses proofreading and content review, forensic consultancy, and creative designs in photography and crafts, with room to grow and evolve just as the world of forensic science has continued to grow and evolve.