Now Reading: Identifying Fingerprints through Photograph: Reliable or Unreliable?

-

01

Identifying Fingerprints through Photograph: Reliable or Unreliable?

Identifying Fingerprints through Photograph: Reliable or Unreliable?

A Fingerprint is an impression formed when the palmar surface of the hand comes in contact with any surface. Such an impression is made up of an arrangement of different pattern styles formed by the raised part of the fingerprint known as the ridges and the recessed part known as the furrows. Because of the random arrangement of these pattern characteristics, fingerprints are unique to every individual. Because fingerprints have the properties of being unique, universal, permanent, inimitable, classifiable, and are found in almost all natures of crime scenes, development and preservation are paramount. (“Virtual Labs”, 2021). With regard to the preservation of fingerprints, methods including the use of casting material, latent print lifts, and photography techniques are primarily used.

Forensic photography is required to document evidence found at the crime scene. Even if the forensic photography is done at the crime scene during tagging, collection, and preservation or within the laboratory during analysis, it permanently records the evidence at the scene of crime. Magnified photographs prove to be useful when comparing microscopic or frangible evidence. Documentation of physical evidence by photography makes it easier for multiple people to analyse evidence at the same time. Photographic documentation, certainly, mitigates the effects of evidence damage or loss. (Redsicker, 2001)

History of Fingerprint Photography

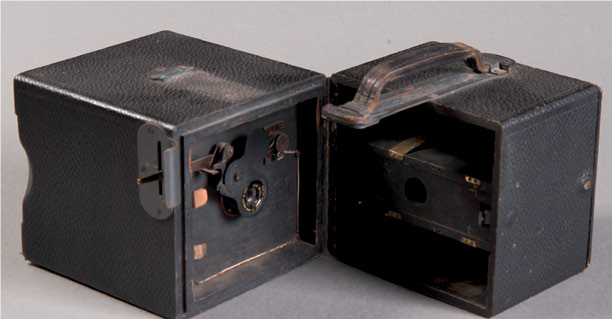

Least as far back in the past century, the New York based Folmer & Schwing Manufacturing Company created the first camera dedicated solely to fingerprinting. With a fixed lens and lights housed in an elliptical case, the camera was completely self-contained. The lamps were activated by shutter movement, exposing the 2″x3″ glass plate, and the lens was positioned at a specific point, producing a focused life-size image on the negative (1:1). (Lightning Powder Co., 2003). The oblong camera’s open-end was placed over the print and the exposure button was pressed to capture a photograph. (Hutchins, 2014)

Fingerprint camera (Hutchins, 2014)

Modern Photography

During forensic investigations, it is critical that no evidence is destroyed or altered as a result of destructive testing, especially in the early stages in order to determine its material properties.

Especially in the case of fingerprints, if the prints are found on challenging surfaces, or in the cases where casts of plastic prints are made, unintentional damage or loss of details is possible and such damage is likely to conceal crucial data gathered in the investigation process.

- Filters can be used to help bring out the definition in the latent prints based on the background colour (light or dark). Prints can occasionally be found on multicoloured backgrounds (soda cans). The most effective strategy is to experiment with different colour filters on the object until you come across a filter that ensures the greatest contrast of the background with the latent print. E.g., Red coloured background can be removed with a red filter No. 25 placed over the camera lens. (Redsicker, 2001)

- Alternative lighting techniques are required if a latent print is found on a mirror, glass, or another reflective surface. 45-degree cross-lighting or a more inclined angle is usually the most efficient method.

- Another method that works well in multicoloured backgrounds is the fluorescent powder, as well as ultraviolet light exposure. A source of long-wave UV light or an electronic flash will suffice.

- Another lighting technique for fluorescent photography that provides maximum illumination is to place a long-wave UV source close to the subject.

- Digital photography- In photography, a digital camera uses a Charge-coupled device (CCD) instead of film to capture an image. The captured image can be instantly checked on the monitor and, if necessary, retaken. (Hutchins, 2014)

Procedure of Photography for prints found in the crime scene

Establish the location of the impression

Patent and plastic prints are easily identified in crime scenes. Latent prints, on the other hand, are frequently overlooked. To avoid that all possible surfaces of contact are taken into account, such as entry and exit points, doorknobs, tables, slabs, and so on.

The exact location of the fingerprint in relation to its surrounding surface should be noted using a mid-range or close-range photograph once it has been located (with a scale). (Staggs,2021).

Exposure: Some patent prints can be photographed using ambient (natural) light. However, depending upon the background, the contrast may be affected unfavourably. When a black powdered fingerprint is photographed against a white background, for example, the camera will underexpose the image, resulting in a loss of detail. The image reflects more light than a typical background because it is mostly white.

The light source could be a photographic laboratory lamp, a photographic slide viewer, an electronic flash, a forensic light source, or a photographic negative viewing light. (Staggs, 2021)

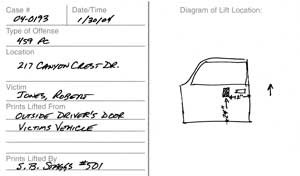

Latent print card showing original location of fingerprint. (Staggs,2021)

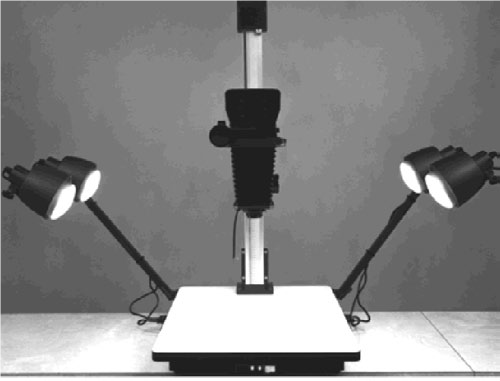

Direct lighting: It is a strong lighting that comes directly from a source rather than being reflected off another surface. This lighting technique provides a great contrast between the light and dark parts of the object being photographed. 2 or 4 lights are balanced and aligned 45 degrees above the object, directly illuminating it. (Hutchins, 2014)

Direct lighting (Hutchins, 2014)

Direct Reflection lighting: In direct reflection lighting, one light source is 10 ° degrees away from the object, and the object is 10 ° away from the lens system. The said approach works best on flat surfaces and produces a lot of distinction with respect to the surface. On a light grey (white) background, latent prints developed with black, grey, or silver powder will always photograph dark (black). (Hutchins, 2014).

Direct Reflection Lighting (Hutchins, 2014)

Front Directional Lighting: The source of light is placed at a right angle to the camera lens’s axis, in front directional lighting (axial or axis lighting). The photographing object is placed directly in front of the camera lens. To direct the light onto an object, a piece of glass is placed at a 45-degree angle in the axis of the camera lens. This technique is employed for photographing the latent prints on mirrors or prints within falciform objects. (Hutchins, 2014)

Front Directional Lighting (Hutchins, 2014)

Cross lighting/Oblique lighting: It is also known as side lighting. To create shadows that show detail, low-angle illumination is employed. A source of light is placed at a low or oblique angle, skimming across the whole surface and emphasising the elevated areas. A second light is required if shadows become a challenge. It is used in ‘Plastic’ or 3D impressions found on surfaces such as wax, clay, soap, butter, soil, etc., (Hutchins, 2014)

Oblique l (Hutchins, 2014)

Close up photograph

Even though there have been specific cameras for documenting finger impressions, photography can also be done with a 35 mm or a high-quality digital camera with a macro lens or any other close–up accessory. The positioning and the stabilisation of the camera are achieved using a Tripod. This is extremely important because the depth of field in close–up photography is shallow. A Tripod-mounted camera allows for precise focusing. To capture the maximum details, a photograph of the latent print is taken such that the surface housing the print is parallel to the film plane of the camera. To acquire as much level of detail on the film as possible, fix the camera at a specific point such that the fingerprint and scale occupy the frame of your viewfinder. (Staggs, 2021)

Reliable or Not?

There are a variety of situations where photography would be a more practical way to acquire identification. In a case where evidence preservation is critical, photographs of the fingerprints can be useful. This allows for identification to be obtained prior to the gathering of evidence without causing the decedent any discomfort. (Schaefer & Frost II, 2021)

The main goal of any challenge would address the fair and accurate representation of the photographic evidence.

Fingerprints have been successfully extracted from photographs on several occasions. It can be relied upon because in cases where fingerprints are obtained from ‘incidental photographs’, no deliberate attempts to alter the friction ridge details are made much.

Fingerprints extracted from such photographs have the following benefits-

- Image Magnification and Enhancement

There are softwares available by which it is possible that work from multiple investigators and sources can be tracked, scaled, compared, enhanced, and printed. In digital imaging, image enhancement is achieved with a scanner that evaluates the pixels surrounding each new pixel to determine what colour it should be for a higher resolution image. (Redsicker, 2001).

- Non-Destructive

It is also the preferred mode of processing and documenting fingerprints in case of bodies undergoing decomposition. During the advanced stages of the decomposition, where the skin is desiccated or requires maceration, removal of the epidermal layer of skin can be worrisome. (Schaefer & Frost II, 2021)

Because the fingertip is a convex surface, photography of the friction ridge detail on the finger frequently employs varying degrees of oblique lighting. The best strategy for luminance and lighting angles for each individual print is usually derived through trial and error, with each finger photographed to narrow it down. (Schaefer & Frost II, 2021)

Use of strong oblique light (Schaefer & Frost II, 2021)

Disaster Victim Identification is another area where this technique can be beneficial (DVI). The recovery, identification, and repatriation of human remains to investigators and the deceased’s families is critical at the scene of any major disaster. Between the time a deceased person or body part is discovered at the disaster scene and the time it is examined at the morgue, there is usually a time delay. (Whyte, 2021)

Image of a decomposed finger Visible details for comparison after photography

(Schaefer & Frost II, 2021)

Case Study

Detectives received information that Dannie Horner, a Sarasota resident, was making graphic child pornography with a child aged 1 year. However, even though Horner was placed under arrest, authorities required proof to prove their case. Investigators discovered photos of Horner and the victim while sorting through the images on the phone; Horner’s face was not visible in any of the child pornography images, but one of his hands was seen holding the camera and the other abusing the child. Horner was already a suspect in the case, so his fingerprints on file were manually compared to the fingerprint detail seen in the photos recovered from the phone. Horner’s fingerprints were stained with paint due to his occupation as an artist, so detectives used computers to isolate and extract them. It turned out to be a perfect match. (Chan, 2021)

Visible details after extracting finger ridge details from a photograph of the accused (Schaefer & Frost II, 2021)

Scientists from the National Institute of Informatics (NII) in Japan recently stated that they were capable of extracting utilisable fingerprints from photographs of bare exposed fingers captured from up to three metres away. (Miura et al., 2016)

There are, of course, difficulties in identifying individuals based on visible friction ridges in images. The fact that the questioned image and the known impression are not calibrated to scale is one such challenge. (Grice & Turnidge, 2021)

When examining fingerprints, the pattern area or the volar pads of the fingers are the most crucial, but in extracting fingerprints from incidental photographs the fingers of the suspect would be occupied with any object, e.g., holding a gun, grasping a basketball bat etc, the pattern area may not be obtained and thus the forensic scientist may have to work with a discontinuous partial print. (Karen Oswald, NIJ sponsored, 2020). Distortions are often caused due to the focal point and lighting of the photograph. Since you have to work with what is provided it will be difficult to extract fingerprints from a photo with an ineffectual point of focus and unfavourable exposure of light. (Karen Oswald, NIJ sponsored, 2020)

Another point of objection is that digital images are easy to manipulate and difficult to detect. For this same reason, the authenticity of digital photographs is always questioned in court, in comparison to photos captured by analog cameras.

Conclusion

With advances in camera and electronic image resolution technology, the random capture of friction ridge skin in images of comparison quality is becoming more common. The popularity of social media sites like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, to name a few, has resulted in an avalanche of publicly available photos. If investigators are aware of what can be done, we can expect to see an increase in these types of identifications in criminal investigations.

Although there are many controversies regarding the manipulation that can be done using modern photoshop technologies, it has to be noted that in most cases the incidental or evidential photographs seized by the investigation team are less likely to be manipulated as the offender would not have expected such a plan of action.

When examining such photographs, we should also be cognizant of any potential situational or contextual bias that could influence the findings as well.

References:

- Virtual Labs. Vlabs.iitb.ac.in. (2021). Retrieved 24 October 2021, from http://vlabs.iitb.ac.in/vlabs-dev/vlab_bootcamp/bootcamp/The_Four_Wizards/labs/exp1/theory.html.

- Redsicker, D. (2001). The practical methodology of forensic photography(2nd ed.,chapter 8). CRC Press.

- Hutchins, L. (2014). The Fingerprint Sourcebook(p. chapter 8). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Lightning Powder Co., Inc. Fingerprint Camera. Minutiae, 2003, 74, 5

- Staggs, S. (2021). Crime Scene and Evidence Photography – Evidence Photography At the Crime Scene. Crime-scene-investigator.net. Retrieved 24 October 2021, from https://www.crime-scene-investigator.net/csp-evidence-photography-at-the-crime-scene.html.

- Schaefer, A., & Frost II, D. (2021). Evidence Technology Magazine. Evidencemagazine.com. Retrieved 24 October 2021, from https://www.evidencemagazine.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1959.

- Whyte, M. (2021). Fingerprint identifications from images and video recovered from cell phones. In The Loop. Retrieved 24 October 2021, from http://www.in-the-loop.net.au/fp-identifications-from-digital-media/.

- Chan, M. (2021). Detectives use fingerprints from photo of suspect’s hand to ID him in child porn case. nydailynews.com. Retrieved 24 October 2021, from https://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/detectives-fingerprints-photo-perp-hand-id-article-1.2268308.

- Grice, C., & Turnidge, S. (2021). Evidence Technology Magazine – Identifying Criminals by Hands Visible in Images. Evidencemagazine.com. Retrieved 24 October 2021, from https://www.evidencemagazine.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=2006.

- Karen Oswald, NIJ sponsored (2020). Case Studies, season 6. Just Identifying Fingerprints Through Photographs_2020 Case Studies_147 [Podcast]. Retrieved from https://soundcloud.com/just_science/just-identifying-fingerprints-through-photographs_2020-case-studies_147.

- Miura, N., Nakazaki, K., Ichige, K., Matsuda, Y., Nagasaka, A., & Miyatake, T. (2016). Non-contact-type Multiple Finger Vein Authentication Based on Visible Light Imaging. In The Sixth Symposium on Biometrics, Recognition and Authentication(pp. 23-24). NII.