Now Reading: The role of Forensic Anthropology in Mass Disaster Victim Identification

-

01

The role of Forensic Anthropology in Mass Disaster Victim Identification

The role of Forensic Anthropology in Mass Disaster Victim Identification

When mass fatalities occur during natural disasters (e.g. tsunamis, earthquakes) or human-made incidents (e.g. aeroplane crashes, bombings, industrial accidents), the challenges for forensic identification are considerable. These situations may exceed typical caseloads; the remains will be disarticulated or burned, and traditional identifying features (e.g., fingerprints, intact faces) may not be available. In this environment, forensic anthropology is crucial. Forensic anthropology is multidisciplinary, drawing on relevant aspects of anatomy, archaeology and forensic science, for the recovery, analysis and identification of human remains. The forensic anthropologist’s expertise is paramount in the absence of a skeleton, which will occur when identifying others means to return the uninhabited name(s) of the deceased. Forensic anthropologists play a vital role in the scene recovery of remains, in triage for recovery of remains, in the biological profile (age, sex, stature, ancestry) of remains, in reconciling postmortem and antemortem information, and a range of additional professional functions. Forensic anthropology is much more than recovery and analysis of bones; it contributes to humanitarian purposes that address the needs of survivors, legal processes, and navigates logistical complexities of mass fatality identification operations.

Background and operational framework:

Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) is organised around phases to ensure organised, thoughtful, science-based, and respectful management of remains. These are: an assessment and recovery phase, a post-mortem documentation and collection phase, an antemortem phase, a reconciliation phase, and finally, a release or disposition phase. Forensic anthropology can contribute to each of the different phases. At the scene, anthropologists can aid in mapping out where the remains are, distinguishing between human and non-human material, assessing fragmentation and commingling of the remains, and advising on ergonomics for recovery of the remains. At the mortuary, anthropologists are involved in sorting, inventorying, and reconstructing the remains, estimating biological profiles, determining viable sample zones for DNA or odontology, documenting trauma and/or pathological characteristics, and all the while documenting the remains. In the reconciliation phase, anthropologists assess if fragmented remains can be re-associated, if skeletal characteristics match documentation surrounding missing persons, and contribute to the final decision on identification of the victim. The involvement of anthropologists facilitates accuracy, reduces turnaround times, and increases the legitimacy of the identification process.

Methods:

Recovery, sorting and reconstruction

The processes of accomplished recovery, sorting and reconstructing disturbed or destroyed remains will be the primary task of the forensic anthropologist. This entails providing a framework and process to the recovery, addressing matters such as mapping grids, establishing the chain-of-custody for remains, using skeletal inventory systems, and employing diagnostic imaging or post-mortem CT scans to find and assess fragments that have become commingled. It will also include the sorting stage, where the forensic anthropologist will distinguish human skeletal remains from animal and environmental debris, assess the completeness of the remains, evaluate the laterality of the remains (side), type of skeletal element, and identify the percentage of fragmentation of the skeletal remains. Reconstruction is either physically reassembling larger skeletal elements or digitally modelling fragments of human remains to provide evidence for matching skeletal elements.

Biological profiling

An essential part of a forensic anthropologist’s job involves preparing a biological profile on each skeleton. This biological profile includes information related to the estimation of age at death (based on pelvic and cranial morphology, dentition, and epiphyseal fusion), sex (based on pelvic morphology and cranial traits), stature (reduced from long bone measurements), and ancestry/population affinity (using cranial measurements or morphological traits). Forensic anthropologists also look for distinctive skeletal traits, such as healed fractures, surgical devices, dental restorations, and/or pathological changes, which may be compared with antemortem records. This area of analysis becomes particularly critical when DNA is degraded or not available.

Integration with Odontology, Radiology and DNA:

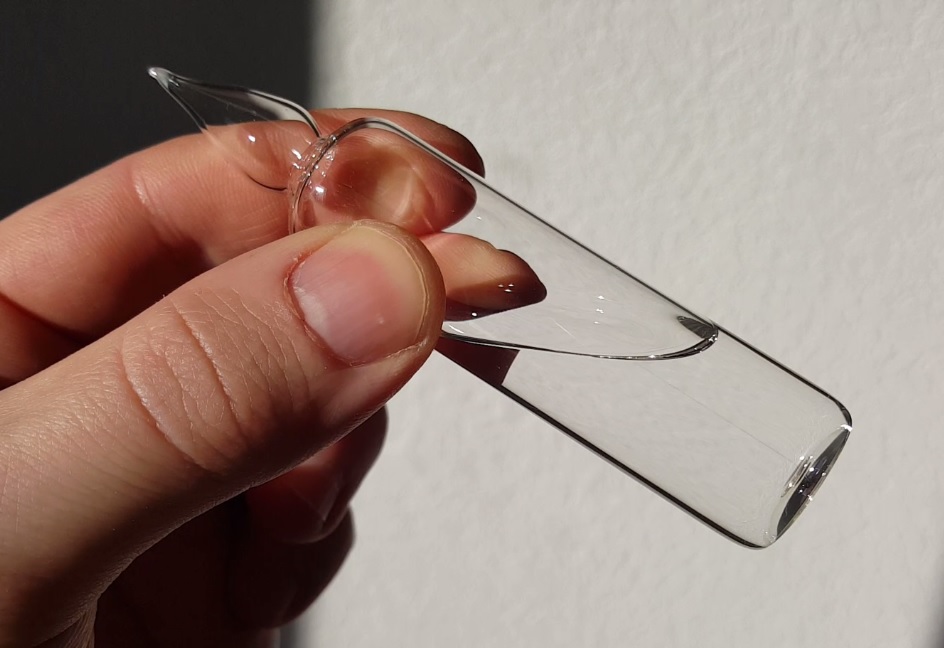

Forensic anthropology almost never works in a vacuum. Successful DVI operations meld anthropology with additional forms of identification, which include, but are not limited to, odontology (using dental records), radiology (post-mortem imaging), and molecular biology (DNA). Anthropologists can identify the skeletal elements that are viable for DNA testing (i.e. dense cortical bone and teeth) and work with odontologists when jaw bones or teeth are available. Radiological imaging can also help support identifying fragments and trauma analysis. By melding these forms of identification with anthropology, anthropologists are helping facilitate a multi-modal approach to identification that increases the probability of success while simultaneously mitigating error or misidentification.

Reconciliation and identification:

During the final phase of a disaster victim identification (DVI) process, anthropologists examine the congruence between corresponding antemortem (i.e., before death) data (e.g. dental records, radiographs, surgical histories, medical implants) and the post-mortem findings. Normally, anthropologists analyse whether fragmented remains could be associated with a given individual, as well as whether any age/sex/stature estimates are consistent with missing person data, and if unique skeletal markers confirm the individual’s identity. This final documentation often requires intensive detail, noting ethical parameters defined by the supervising forensic anthropologist, such as integrity of the chain of custody, peer-review hierarchies, and thorough communication with family liaison teams. Once a supervising forensic anthropologist has appointed anthropologists, their dedication to critical thinking contributes to developing decisions that incorporate multiple streams of evidence (bones, teeth, DNA, and personal effects), resulting in a case that yields biologically positive verification.

Future directions:

The advancements in technology, standardisation, and globalisation will guide the future of forensic anthropology in DVI. 3D imaging and virtual anthropology will revolutionise fragment reconstruction and visual documentation, while allowing for digital matching of skeletal elements and implants. AI and machine learning techniques are being tested for the purposes of using skeletal scans for automated age, sex, or ancestry estimation. Stable isotope and trace element analysis of bone and teeth have the potential to trace the geographic origin or migration history of unknown remains. Additionally, global databases of DNA, dental and anthropological information may facilitate faster cross-border identifications in international disasters. Training protocol, quality assurance standards, and international collaboration remain a work in progress, and collaborative efforts will continue to reinforce consistent practices across jurisdictions.

Conclusion:

Forensic anthropology continues to be a cornerstone field in identifying victims from mass fatality events. Byutilisingg anatomical knowledge, archaeological techniques, radiological tools, and archaeological recovery practices, anthropologists assist in bringing some order to the disorder that follows mass death scenarios. Their function is to bridge science and humanity, permitting both the rigour of science and compassionate involvement. In the context of DVI operations, anthropologists attempt to adhere to recognising every fragment, every marker, and every decedent’s narrative with respect and methodological care. As technologies advance, anthropologists’ ability to be interdisciplinary will only grow, continuing to provide names to the nameless and dignity to the dead.