Now Reading: Policy X-Ray: Why Modi Govt’s proposed amendment in Constitution to give 10% quota to upper-caste fails legal test

-

01

Policy X-Ray: Why Modi Govt’s proposed amendment in Constitution to give 10% quota to upper-caste fails legal test

Policy X-Ray: Why Modi Govt’s proposed amendment in Constitution to give 10% quota to upper-caste fails legal test

The Union Cabinet on Monday cleared 10 per cent reservation in jobs and education for economically weaker sections of the upper castes, a gambit intended to consolidate its traditionally loyal vote bank, a large chunk of which was reported to have voted against it in the recent assembly elections.

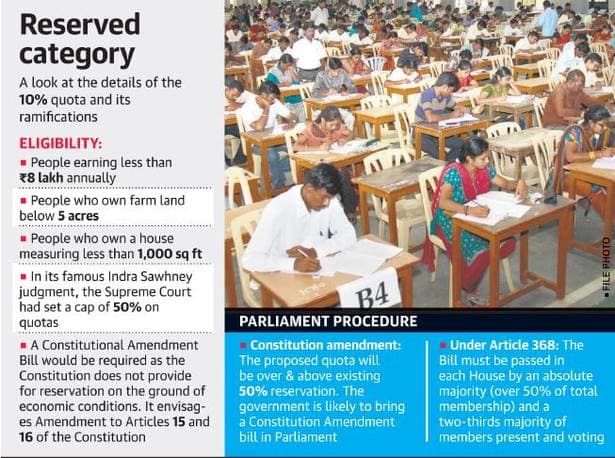

The proposed criteria for determining which families would qualify for the “economically weaker” tag are as follows: an annual income below Rs 8 lakh; farmland less than 5 acres; residential house below 1,000sqft; residential plot below 100 square yards in a notified municipality; residential plot below 200 square yards in a non-notified municipality area.

Source: The Hindu

The Union cabinet on Monday gave its nod for tabling a constitutional amendment bill to provide 10 per cent reservation in government jobs and educational institutions to the “economically weaker sections”. The existing quotas, driven by the principle of social justice, will not be affected, sources said.

A similar proposal had been made by the P.V. Narasimha Rao government in 1991, but it was struck down by the Supreme Court on constitutional grounds.

For announcement, it is a great liner for seeking vote bank but in reality it is unworkable, as it needs in both house of parliament and state assemblies to ratify as it will be a constitutional amendment. Articles 15 and 16 of the Constitution will have to be amended for implementation of the decision.

Reports say the quota will be over and above the existing 50 per cent reservation, and thus, won’t impact the fate of the reserved communities.

An amendment of the Constitution can be initiated only by the introduction of a Bill in either House of Parliament. The Bill must then be passed in each House by a majority of the total membership of that House and by a majority of not less than two-thirds of the members of that House present and voting. There is no provision for a joint sitting in case of disagreement between the two Houses. The Bill, passed by the required majority, is then presented to the President who shall give his assent to the Bill. If the amendment seeks to make any change in any of the provisions mentioned in the proviso to article 368, it must be ratified by the Legislatures of not less than one-half of the States. Although there is no prescribed time limit for ratification, it must be completed before the amending Bill is presented to the President for his assent.

Supreme court ruled that the constituent power under Article 368 pf Constitution of India must be exercised by the Parliament in the prescribed manner and cannot be exercised under the legislative powers of the Parliament. (“Para 506e of Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, (AIR 1973 SC 1461)

Article 368. Power of Parliament to amend the Constitution and Procedure therefor:

- (1) Notwithstanding anything in this Constitution, Parliament may in exercise of its constituent power amend by way of addition, variation or repeal any provision of this Constitution in accordance with the procedure laid down in this article.

- (2) An amendment of this Constitution may be initiated only by the introduction of a Bill for the purpose in either House of Parliament, and when the Bill is passed in each House by a majority of the total membership of that House and by a majority of not less than two-thirds of the members of that House present and voting, it shall be presented to the President who shall give his assent to the Bill and thereupon the Constitution shall stand amended in accordance with the terms of the Bill:

- Provided that if such amendment seeks to make any change in –

- (a) article 54, article 55, article 73, article 162 or article 241, or

- (b) Chapter IV of Part V, Chapter V of Part VI, or Chapter I of Part XI, or

- (c) any of the Lists in the Seventh Schedule, or

- (d) the representation of States in Parliament, or

- (e) the provisions of this article,

- the amendment shall also require to be ratified by the Legislatures of not less than one-half of the States by resolutions to that effect passed by those Legislatures before the Bill making provision for such amendment is presented to the President for assent.

- (3) Nothing in article 13 shall apply to any amendment made under this article.

- (4) No amendment of this Constitution (including the provisions of Part III) made or purporting to have been made under this article whether before or after the commencement of section 55 of the Constitution (Fortysecond Amendment) Act, 1976 shall be called in question in any court on any ground.

- (5) For the removal of doubts, it is hereby declared that there shall be no limitation whatever on the constituent power of Parliament to amend by way of addition, variation or repeal the provisions of this Constitution under this article.

Also, It is to be noted that Hon’ble Supreme Court had made it clear that reservation can’t go beyond 50%.

The Indira Sawhney judgment declared 50% quota as the rule unless extraordinary situations “inherent in the great diversity of this country and the people” happen. Even then, extreme caution is to be exercised and a special case should be made out.

If the government proposes to bring a constitutional amendment to include the 10% quota for “unreserved economically weaker sections”, the 11-judge Kesavananda Bharati judgment may stand in the way. The judgment held that constitutional amendments which offended the basic structure of the Constitution would be ultra vires. Neither Parliament nor legislatures could transgress the basic feature of the Constitution, namely, the principle of equality enshrined in Article 14.

The government, it is reported, proposes to bring the 10% over and above the 49% quota — 7% for Scheduled Castes, 15% for Scheduled Tribes and 27% for Socially and Educationally Backward Classes, including widows and orphans of any caste, which is permitted. But a total 59% (49%+10%) quota would leave other candidates with just 41% government jobs or seats. This may amount to “sacrifice of merit” and violate Article 14.

In the Indra Sawhney vs Union of Indian case (Mandal Commission case), a nine-judge bench of the apex court wrote that Kalelkar “opined that the principle of caste should be eschewed altogether. Then alone, he said, would it be possible to help the extremely poor and deserving members of all communities.”

The Mandal Commission, which followed Kalelkar Commission in 1979, submitted its report in December 1980. It recommended extending reservation benefits to socially and educationally backward classes (SEBC). Implementing it, the V P Singh government issued an Office Memorandum (OM) on August 13, 1990, directing that “27% of vacancies in civil posts and services under the Government of India shall be reserved for SEBC”.

Following protests against its implementation, petitions were filed challenging the OM. The court stayed the decision.

After the P V Narasimha Rao government came in in 1991, another OM was issued on September 25, 1991, modifying the earlier memorandum. The new OM said that “10% vacancies in civil posts and services under the Government of India shall be reserved for other economically backward sections of the people who are not covered by any existing schemes of reservation”.

The apex court struck this down while deciding the Mandal Commission judgment.

The court, which went into various Constitutional provisions on the reservation, noted, “…identification of such class cannot be caste based. Nor it can be founded, only, on economic considerations, as ‘mere poverty’ cannot be the test of backwardness.”

Striking down the provision, the court said, “This clause provides for 10% reservation (in appointments/posts) in favour of economically backward sections among open competition (non-reserved) category. Though the criteria is not yet evolved by the Government, it is obvious that the basis is either income of a person and/or the extent of property held by him. The impugned Memorandum does not say whether this classification is made under Clause (4) or Clause (1) of Article 16… we find it difficult to sustain.”

The top court observed, “Reservation of 10% vacancies among open competition candidates on the basis of income/property-holding means exclusion of those above the demarcating line from those 10% seats. The question is whether this is constitutionally permissible. We think not. It may not be permissible to debar a citizen from being considered for appointment to an office under the State solely on the basis of his income or property-holding. Since employment under the State is really conceived to serve the people (that it may also be a source of livelihood is secondary), no such bar can be created…”

Union Law Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad has clarified that to implement the cabinet’s decision to start giving 10 per cent reservation to ‘economically-backward’ upper castes in government jobs, the Centre will bring in a constitutional amendment and not a legal one.

Prasad was responding to former union minister and Congress leader Manish Tewari at the launch of former MP Baijayant Panda’s book, Lutyens’ Maverick.

“The threshold to define economically disadvantaged persons is surprisingly high. Families with income less than Rs 8 lakh annually (or Rs 66,666 rupees monthly), or less than five acres of land, would qualify. These are very far from the poorest of the poor; instead, they would cover more than 75 per cent of households in the country. By contrast, India’s poverty line is marked at a dollar a day. If the government was serious in reaching out to the most economically vulnerable, its cut-off should have been much lower.” –Harsh Mander, Retd IAS officer and social activist told The Print

The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) released a startling figure of 11 million job losses in 2018 alone. In Parliament, the government has acknowledged that there are 24 lakh vacancies in various state and central department.

So a question arises, When there is NO JOBS creation and already 24 Lakh vacancies in govt sector which are not filled by the Govt, then Country need to debate for Reservation or Jobs?